Cheating or self-teaching?

When a student argues that copying school work off the Internet isn’t cheating, but ‘self-teaching’, one is tempted to dismiss this as another example in the time-honoured tradition of lame excuses. When the head of a group in charge of British qualifications says the same thing, it makes one sit up and take notice.

‘People are open to download essays from the Internet. They can then change the language and grammar and put in their own words, but if people are going to that effort they are essentially taking part in self-teaching; they are learning the subject anyway,’ said Dr. Ellie Johnson Searle, director of the Joint Council for Qualifications, the body that represents the main exam boards in the United Kingdom. The comments were made during a BBC radio interview. You could already hear legions of teachers recoiling in shock and horror, spilling their tea onto the staff room floor.

The above begs the question: what exactly is cheating? When I asked a series of teachers and students to give me examples of cheating, the four most popular were:

• copying off a friend • copying off prepared notes • whispering a question or answer to a friend • using a learning aid (calculator, or dictionary for example)

Most teachers and students immediately associated cheating with an exam situation.

This is because, of course, exam situations are the bane of most students’ lives. Exam anxiety is not something that people grow out of either. On a LTCL Diploma course in TESOL that I tutor for in Barcelona, the majority of teachers — who have spent at least two years teaching and administrating exams — become incredibly stressed as the final exam approaches. In response to stressful situations, people develop coping strategies. Cheating is one of the more negative coping strategies people resort to in assessment situations.

The whole issue of examining and cheating is an important one for language teachers. This is because so much of our work is involved in helping students develop tools to communicate and learn language that would be thought of as cheating in an exam situation. Working in pairs, asking a colleague for help, and asking for feedback on errors from the teacher are all regular features of the modern communicative classroom. Then there is the whole area of ‘learner training’ in ELT: making useful notes, consulting a dictionary, recording language in different ways to refer back to. Couldn’t all these also be what Dr. Johnson Searle would call ‘self-teaching’? And yet all the above would be considered cheating in most traditional exams.

What are language teachers to do to reconcile this difference between what the teacher lauds as good practice inside and outside the classroom, but pounces on during a testing situation (arguably more important in the minds of many students)? There are different options open to the language teacher:

1 Eliminate all exams and move to a different form of assessment

This is a progressive and humanistic option, given the shortcomings of exams and their negative effects in language learning situations. But what form will the assessment take? Many schools would balk at the idea of having assessment done any other way, partly because it would be quite difficult to set up. Exams are also seen as a handy way of standardising performance.2 Make exams ‘cheat-proof’

This entails reducing the number of questions which have only one possible answer and making the exam much more personalised to the students. Copying becomes much more difficult in this case. The difficulty here is that such exams are quite difficult to mark, especially for the busy teacher.3 Strictly control exam situations so that cheating cannot occur

Add more invigilators to the exam room. Grow eyes in the back of your head. Prowl around the desks like a tiger waiting to pounce on the cheaters. These are in fact the most popular ways of controlling cheating behaviour. But they create an atmosphere of tension and conflict, two factors that the exam situation very stressful for both teachers and learners.4 Let cheating happen

This is the most revolutionary option, and it brings us back to Dr. Searle’s assertions. First, I should make it clear that this doesn’t mean a ‘no rules’ approach to exams. That is not what I am suggesting. Neither, in fact, is Dr. Searle, who said in the same interview that the penalties for cheating depended on ‘the extent of the cheating. If the plagiarism becomes the substance of the work, in extreme cases, a pupil would be barred.’

I believe that being proactive about cheating, and allowing it to occur under controlled circumstances, will ultimately help learners in exam situations. Here are a couple of practical examples of the kind of cheating I am speaking about.

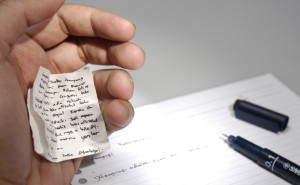

1 Prepared crib notes

Tell your students that for the next test they will be allowed to make a crib note, which they can bring into the exam. I often say that each person is allowed one A4-size piece of paper on which they can write anything and as much as they like (on one side). The only other rule is that everything must be in their own handwriting (no photocopies). To make it more challenging, you could reduce the size of the paper (half an A4 sheet) or allow them to write on one side only.2 Dictionary run

Allow students to use a dictionary for the exam. If you think that they would spend too long with it, then allow a dictionary ‘run’ during the exam, in which they can ask you to lend them a dictionary for a period of three minutes, for example.

I have found that, in my classes, when I incorporate one or both of the above options into the exam, there are no noticeable differences in results (meaning that those who would fail before still fail). There are, however, noticeable differences in attitudes and stress levels before the exam (i.e. they are lower). The interesting thing about the crib note is that, in the heat of the exam, many do not use it. They had spent so long preparing it laboriously that they knew it all off by heart. As for the dictionary use, I have never seen my students use their dictionaries so well and so fast. As Dr. Searle said, ‘they are learning it anyway’. And that’s the whole point of teaching, isn’t it?

For a BBC article about copying and self-teaching, see this website:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/education/3598161.stm

Another similar essay on cheating and cooperative learning can be found at: http://www.jnd.org/dn.mss/InDefenseOfCheating.html

You can read a great article by Mario Rinvolucri on the Strange World of EFL testing at: http://www.longman.com/longman_turkey/university/yourarticlesnew.html

A summary of learner training and learner autonomy can be found on this site:

http://iteslj.org/Techniques/McCarthy-Autonomy.html

You can read an earlier short article which includes some of the ideas presented above in ‘You Cheat’ by Lindsay Clandfield (English Teaching Professional, April 2003).

This article originally appears at http://www.macmillandictionaries.com/MED-Magazine/June2004/20-Feature-Cheating.htm